What the Likelihood of Seeing a Person Again

What does it take to succeed? What are the secrets of the most successful people? Judging by the popularity of magazines such as Success, Forbes, Inc., and Entrepreneur, there is no shortage of interest in these questions. There is a deep underlying assumption, however, that nosotros can learn from them because it'southward their personal characteristics--such as talent, skill, mental toughness, difficult work, tenacity, optimism, growth mindset, and emotional intelligence-- that got them where they are today. This assumption doesn't just underlie success magazines, but also how we distribute resources in society, from piece of work opportunities to fame to regime grants to public policy decisions. We tend to give out resources to those who have a by history of success, and tend to ignore those who accept been unsuccessful, assuming that the most successful are as well the most competent.

But is this assumption correct? I have spent my entire career studying the psychological characteristics that predict achievement and creativity. While I have constitute that a sure number of traits-- including passion, perseverance, imagination, intellectual curiosity, and openness to experience-- do significantly explain differences in success, I am oft intrigued past simply how much of the variance is often left unexplained.

In contempo years, a number of studies and books--including those by risk analyst Nassim Taleb, investment strategist Michael Mauboussin, and economist Robert Frank-- have suggested that luck and opportunity may play a far greater part than nosotros always realized, across a number of fields, including financial trading, business, sports, art, music, literature, and science. Their argument is not that luck is everything; of form talent matters. Instead, the information suggests that we miss out on a really importance piece of the success motion-picture show if we only focus on personal characteristics in attempting to sympathise the determinants of success.

Consider some contempo findings:

- Well-nigh one-half of the differences in income across people worldwide is explained past their land of residence and past the income distribution within that state,

- Scientific bear on is randomly distributed, with high productivity alone having a limited effect on the likelihood of high-impact work in a scientific career,

- The chance of becoming a CEO is influenced by your name or calendar month of birth,

- The number of CEOs born in June and July is much smaller than the number of CEOs born in other months,

- Those with last names earlier in the alphabet are more than likely to receive tenure at top departments,

- The display of middle initials increases positive evaluations of people's intellectual capacities and achievements,

- People with easy to pronounce names are judged more positively than those with difficult-to-pronounce names,

- Females with masculine sounding names are more successful in legal careers.

The importance of the subconscious dimension of luck raises an intriguing question: Are the almost successful people mostly just the luckiest people in our society? If this were even a picayune bit true, then this would have some significant implications for how nosotros distribute express resources, and for the potential for the rich and successful to really benefit society (versus benefiting themselves by getting even more rich and successful).

In an attempt to shed light on this heavy consequence, the Italian physicists Alessandro Pluchino and Andrea Raspisarda teamed up with the Italian economist Alessio Biondo to brand the first e'er endeavour to quantify the part of luck and talent in successful careers. In their prior work, they warned against a "naive meritocracy", in which people really neglect to requite honors and rewards to the most competent people considering of their underestimation of the role of randomness among the determinants of success. To formally capture this miracle, they proposed a "toy mathematical model" that simulated the development of careers of a collective population over a worklife of forty years (from age twenty-60).

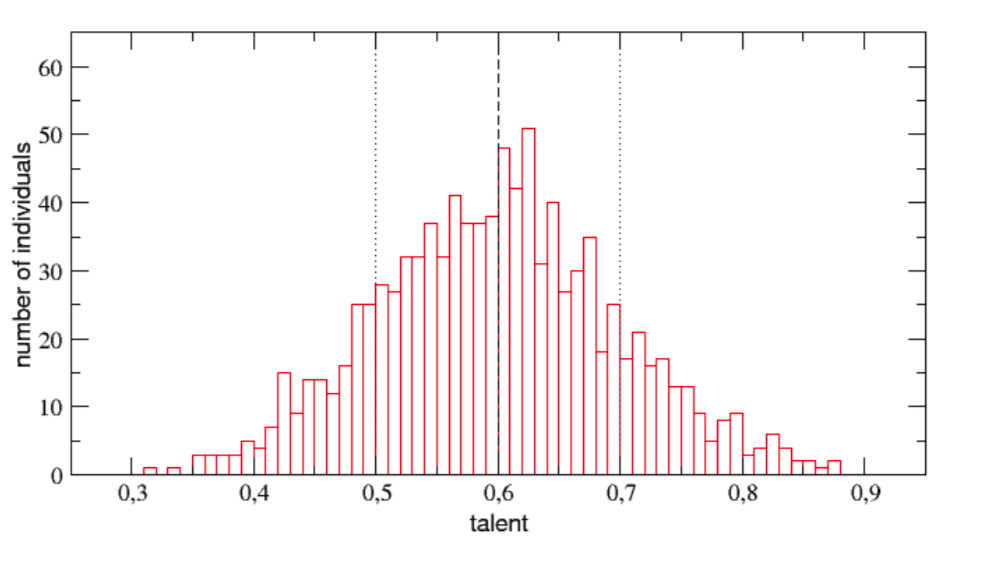

The Italian researchers stuck a large number of hypothetical individuals ("agents") with different degrees of "talent" into a square world and permit their lives unfold over the grade of their unabridged worklife. They defined talent as whatever ready of personal characteristics permit a person to exploit lucky opportunities (I've argued elsewhere that this is a reasonable definition of talent). Talent can include traits such equally intelligence, skill, motivation, determination, creative thinking, emotional intelligence, etc. The key is that more talented people are going to exist more likely to get the nigh 'blindside for their buck' out of a given opportunity (come across here for support of this assumption).

All agents began the simulation with the same level of success (10 "units"). Every 6 months, individuals were exposed to a sure number of lucky events (in light-green) and a certain amount of unlucky events (in red). Whenever a person encountered an unlucky effect, their success was reduced in half, and whenever a person encountered a lucky outcome, their success doubled proportional to their talent (to reflect the real-world interaction between talent and opportunity).

What did they find? Well, starting time they replicated the well known "Pareto Principle", which predicts that a small number of people will finish up achieving the success of most of the population (Richard Koch refers to information technology as the "eighty/20 principle"). In the last outcome of the xl-yr simulation, while talent was normally distributed, success was not. The twenty most successful individuals held 44% of the full corporeality of success, while almost one-half of the population remained under 10 units of success (which was the initial starting condition). This is consequent with real-world data, although there is some suggestion that in the real world, wealth success is even more unevenly distributed, with just eight men owning the same wealth as the poorest half of the globe.

.png)

Although such an unequal distribution may seem unfair, it might be justifiable if it turned out that the nearly successful people were indeed the most talented/competent. So what did the simulation find? On the one hand, talent wasn't irrelevant to success. In general, those with greater talent had a higher probability of increasing their success by exploiting the possibilities offered by luck. Also, the about successful agents were mostly at least average in talent. So talent mattered.

All the same, talent was definitely not sufficient because the most talented individuals were rarely the most successful. In general, mediocre-but-lucky people were much more successful than more-talented-just-unlucky individuals. The near successful agents tended to be those who were only slightly higher up average in talent but with a lot of luck in their lives.

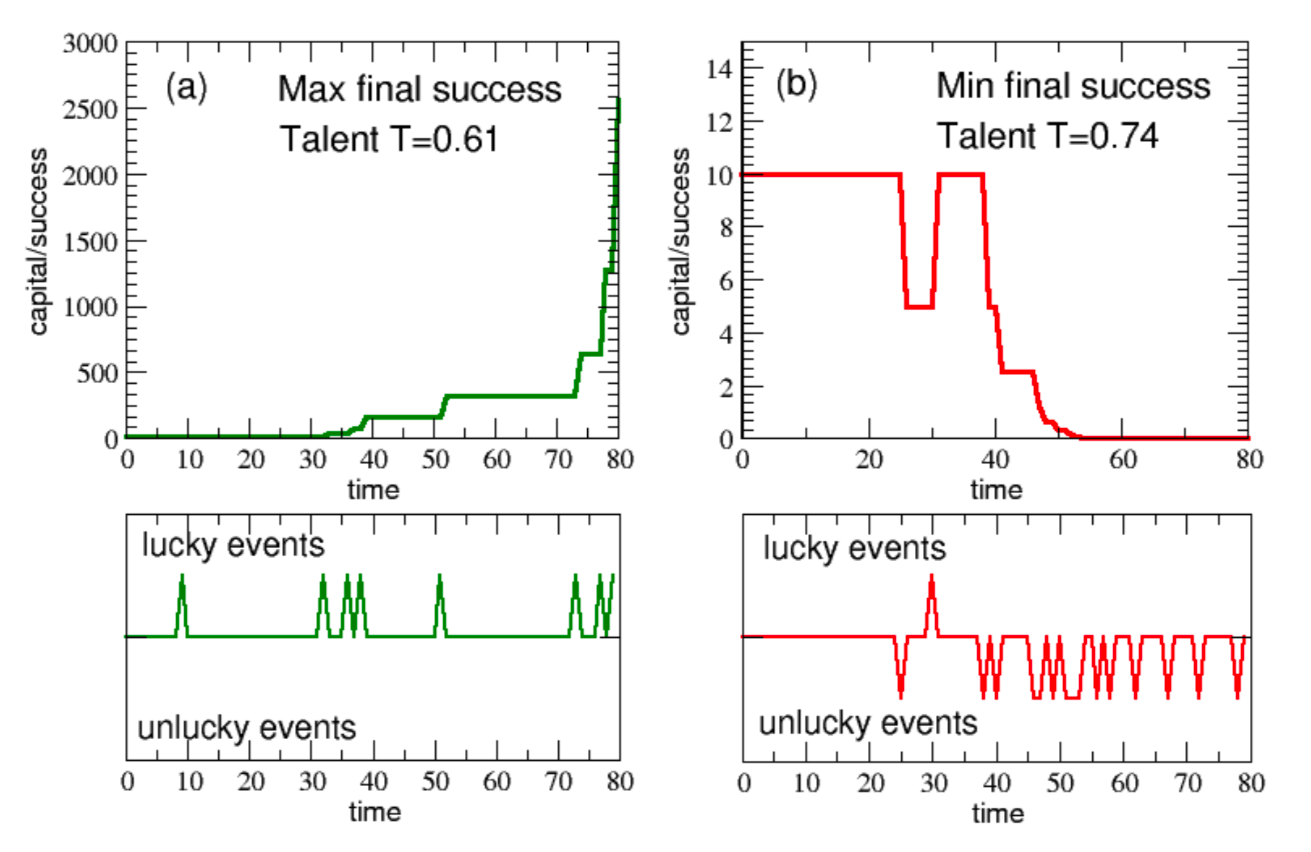

Consider the development of success for the most successful person and the least successful person in one of their simulations:

Equally yous tin see, the highly successful person in green had a serial of very lucky events in their life, whereas the least successful person in red (who was even more talented than the other person) had an unbearable number of unlucky events in their life. Every bit the authors note, "even a great talent becomes useless against the fury of misfortune."

Talent loss is patently unfortunate, to both the private and to order. So what can be done so that those most capable of capitalizing on their opportunities are given the opportunities they almost need to thrive? Let'due south turn to that next.

Stimulating Serendipity

Many meritocratic strategies used to assign honors, funds, or rewards are oft based on the past success of the person. Selecting individuals in this way creates a state of affairs in which the rich get richer and the poor go poorer (often referred to as the "Matthew event"). Just is this the most effective strategy for maximizing potential? Which is a more effective funding strategy for maximizing bear on to the world: giving big grants to a few previously successful applicants, or a number of smaller grants to many average-successful people? This is a fundamental question nearly distribution of resources, which needs to be informed past actual data.

Consider a study conducted by Jean-Michel Fortin and David Currie, who looked at whether larger grants lead to larger discoveries. They institute a positive, but only very pocket-sized human relationship between funding and touch on (as measured by iv indices relating to scientific publications). What's more, those who received a 2nd grant were not more than productive than those who just received a first grant, and bear upon was generally a decelerating function of funding.

The authors propose that funding strategies that focus more on targeting multifariousness than "excellence" are likely to be more productive to gild. In a more recent study, researchers looked at the funding provided to 12,720 researchers in Quebec over a fifteen yr period. They concluded that "both in terms of the quantity of papers produced and of their scientific impact, the concentration of inquiry funding in the hands of a so-called 'elite' of researchers by and large produces diminishing marginal returns."

Taking these sort of findings seriously, the European Research Council recently gave the biochemist Ohid Yaqub 1.seven million dollars to properly determine the extent of serendipity in science. Coming upwards with a multidimensional definition of serendipity, Yaqub pinned down some of the mechanisms by which serendipity in science happens, including astute observation, "controlled sloppiness" (allowing unexpected events to occur while tracking their origins), and the collaborative action of networks of scientists. This is consequent with Dean Simonton'southward extensive piece of work on the role of serendipity and take chances in the evolution of creative and impactful scientific discoveries.

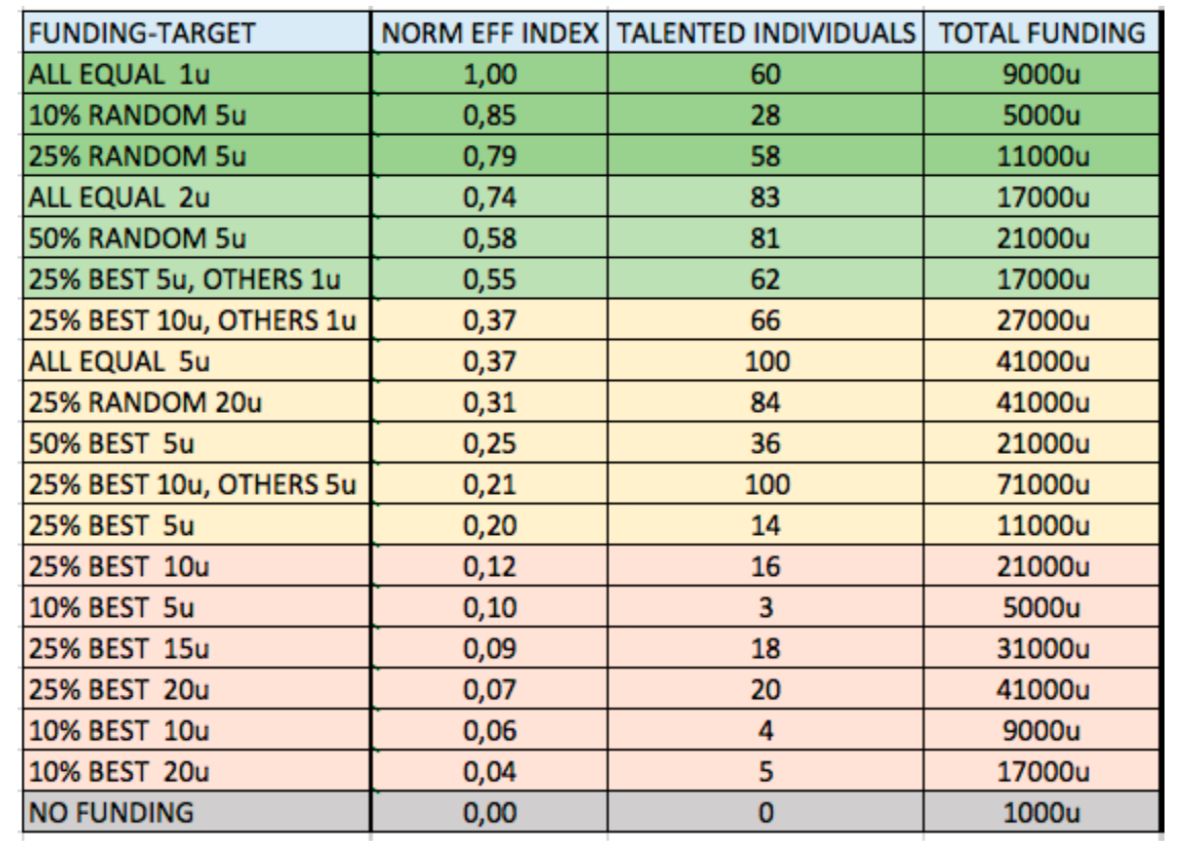

Edifice on this piece of work, the Italian team who simulated the role of luck in success went one step further in their simulation. Playing God (so to speak), they explored the effectiveness of a number of different funding strategies. They applied different strategies every five years during the 40 year worklife of each agent in the simulation. Without any funding at all, nosotros already saw that the most successful agents were very lucky people with about average levels of talent. What happens once they introduced various funding opportunities into the simulation?

This tabular array reveals the well-nigh efficient funding strategies over the 40 yr menstruation in descending order of efficiency (i.east., requiring the least amount of funding for the greatest return on the investment). Starting at the bottom of the list, you lot tin see that the least constructive funding strategies are those that requite a sure pct of the funding to only the already most successful individuals. The "mixed" strategies that combine giving a sure percentage to the most successful people and equally distributing the rest is a bit more than effective, and distributing funds at random is even more efficient. This last finding is intriguing considering it is consistent with other research suggesting that in circuitous social and economic contexts where chance is likely to play a office, strategies that comprise randomness can perform better than strategies based on the "naively meritocratic" approach.

With that said, the best funding strategy of them all was one where an equal number of funding was distributed to anybody. Distributing funds at a charge per unit of i unit every five years resulted in 60% of the almost talented individuals having a greater than average level of success, and distributing funds at a rate of five units every v years resulted in 100% of the most talented individuals having an impact! This suggests that if a funding agency or government has more than coin bachelor to distribute, they'd be wise to utilize that extra coin to distribute money to everyone, rather than to only a select few. As the researchers conclude,

"[I]f the goal is to reward the most talented person (thus increasing their last level of success), it is much more convenient to distribute periodically (even small) equal amounts of capital to all individuals rather than to give a greater capital only to a small per centum of them, selected through their level of success - already reached - at the moment of the distribution."

Stimulating the Environment

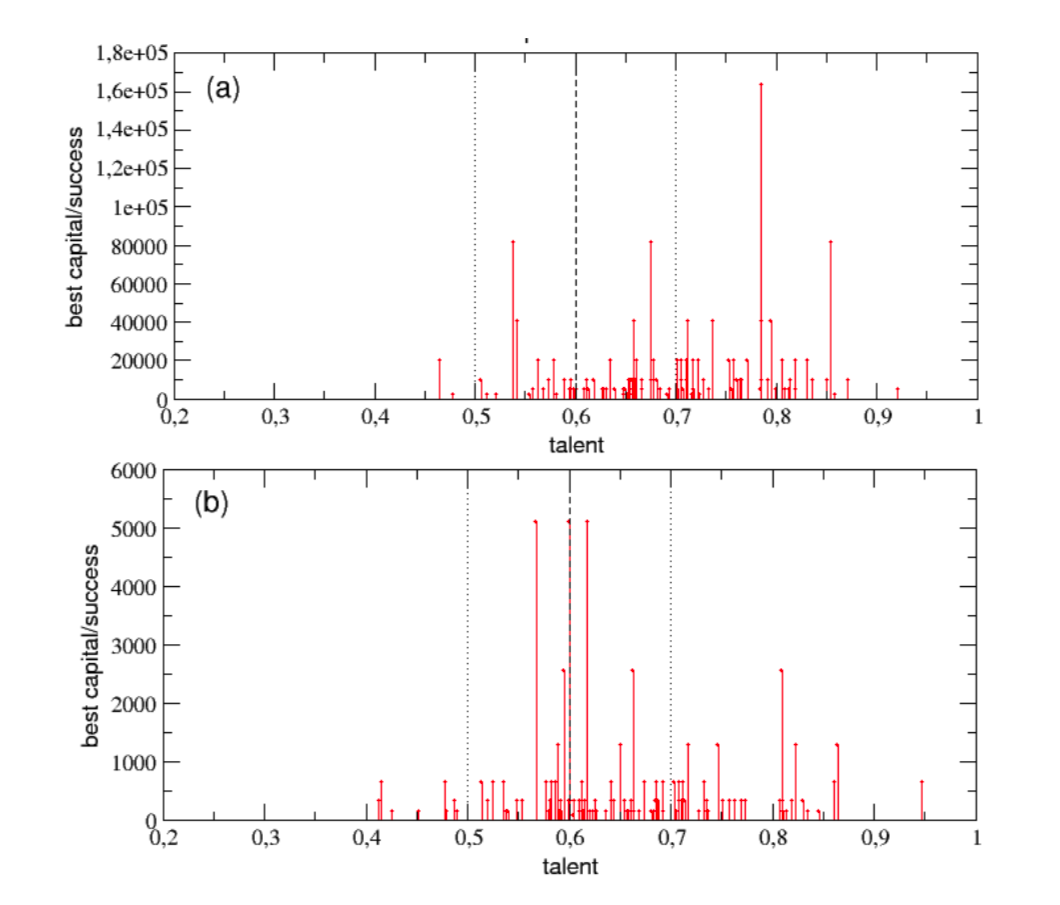

This incredible Italian squad didn't even terminate there! Hey, if yous're playing God, why not get all the way. :) They also ran simulations in which they varied the environment of the agents. Using this framework, they simulated either a very stimulating environment, rich of opportunities for everyone (like that of rich and industrialized countries such as the U.S.) also as a much less stimulating surround, with very few opportunities (similar that of Third World countries). Here's what they institute:

Await at the difference between the outcome distribution of the environment rich in opportunities for everyone (pinnacle) from the outcome distribution of the environment poor in opportunities for everyone (bottom). In the universe fake at the summit, a number of medium to highly talented individuals were able to achieve very high levels of success, and the average number of medium-highly talented individuals who reached at least higher up average levels of success was quite high. In dissimilarity, in the universe simulated at the bottom of the effigy, the overall level of success of the order was low, with an boilerplate of only 18 individuals able to increment their initial level of success.

Decision

The results of this elucidating simulation, which dovetail with a growing number of studies based on real-world data, strongly suggest that luck and opportunity play an underappreciated part in determining the final level of individual success. As the researchers signal out, since rewards and resources are normally given to those who are already highly rewarded, this often causes a lack of opportunities for those who are most talented (i.e., have the greatest potential to actually benefit from the resource), and it doesn't take into account the important role of luck, which can sally spontaneously throughout the creative process. The researchers fence that the following factors are all important in giving people more than chances of success: a stimulating surround rich in opportunities, a good education, intensive training, and an efficient strategy for the distribution of funds and resources. They argue that at the macro-level of analysis, whatsoever policy that can influence these factors volition result in greater collective progress and innovation for order (not to mention immense cocky-actualization of any particular private).

© 2018 Scott Barry Kaufman, All Rights Reserved

Note: One suggestion I fabricated to the Italian team is for their future simulations to take into account the real-world finding that talent develops over time, and is not a fixed quantity of the individual. They graciously said this was a valid point and would definitely accept that into consideration in their future work.

The views expressed are those of the writer(southward) and are non necessarily those of Scientific American.

Source: https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/beautiful-minds/the-role-of-luck-in-life-success-is-far-greater-than-we-realized/

0 Response to "What the Likelihood of Seeing a Person Again"

Publicar un comentario