Did Washington Command the Army Again in 1798 Again

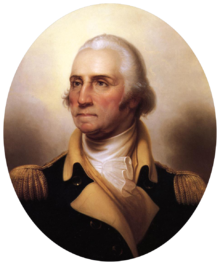

| General of the Armies George Washington | |

|---|---|

Portrait of George Washington in armed services uniform, painted by Rembrandt Peale, c. 1850 | |

| Born | (1732-02-22)February 22, 1732 Westmoreland Canton, Virginia |

| Died | December xiv, 1799(1799-12-xiv) (aged 67) Mount Vernon |

| Fidelity | |

| Years of service | 1752–1758 – British provincial militia 1775–1783 – Continental Army 1798–1799 – United States Army |

| Rank | General of the Armies of the United States 1976–present (posthumous) |

| Commands held | Colonel, Virginia Regiment General and Commander-in-master, Continental Army Commander-in-chief, United states Ground forces |

The military career of George Washington spanned over twoscore years of service. Washington's service can be broken into iii periods, French and Indian War, American Revolutionary War, and the Quasi-State of war with France, with service in three dissimilar military (British provincial militia, the Continental Army, and the United states Army).

Because of Washington's importance in the early history of the Usa of America, he was granted a posthumous promotion to General of the Armies of the United States, legislatively defined to be the highest possible rank in the United states of america Ground forces, more than 175 years after his death.

French and Indian State of war service [edit]

Washington'south 1754 map showing Ohio River and surrounding region

Virginia'southward Royal Governor, Robert Dinwiddie, appointed Washington a major in the provincial militia in February 1753.[i] [two] In that twelvemonth the French began expanding their armed forces command into the "Ohio Land", a territory also claimed by the British colonies of Virginia and Pennsylvania. These competing claims led to a world state of war 1756–63 (called the French and Indian War in the colonies and the Seven Years' War in Europe) and Washington was at the centre of its outset. The Ohio Visitor was one vehicle through which British investors planned to expand into the territory, opening new settlements and building trading posts for the Indian merchandise. Governor Dinwiddie received orders from the British regime to warn the French of British claims, and sent Major Washington in late 1753 to evangelize a alphabetic character informing the French of those claims and asking them to leave.[3] Washington also met with Tanacharison (as well chosen "Half-King") and other Iroquois leaders allied to Virginia at Logstown to secure their support in case of disharmonize with the French; Washington and One-half-King became friends and allies. Washington delivered the letter of the alphabet to the local French commander, who politely refused to leave.[4]

Governor Dinwiddie sent Washington dorsum to the Ohio Land to protect an Ohio Company grouping edifice a fort at present-mean solar day Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Before he reached the area, a French force drove out the company's crew and began structure of Fort Duquesne. With Mingo allies led by Tanacharison, Washington and some of his militia unit ambushed a French scouting party of some 30 men, led by Joseph Coulon de Jumonville; Jumonville was killed, and in that location are contradictory accounts of his death.[five] The French responded by attacking and capturing Washington at Fort Necessity in July 1754.[half dozen] He was allowed to render with his troops to Virginia. The experience demonstrated Washington's bravery, initiative, inexperience and impetuosity.[7] [eight] These events had international consequences; the French defendant Washington of assassinating Jumonville, who they claimed was on a diplomatic mission similar to Washington'due south 1753 mission.[nine] Both French republic and Britain responded past sending troops to North America in 1755, although state of war was not formally declared until 1756.[x]

Braddock disaster 1755 [edit]

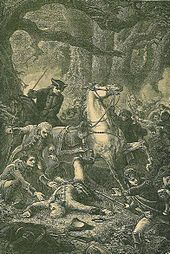

Major-General Braddock's death at the Boxing of the Monongahela, July nine, 1755.

In 1755, Washington was the senior Colonial aide to British General Edward Braddock on the ill-fated Braddock Expedition. This was at the fourth dimension the largest ever British war machine expedition ventured into the colonies, and was intended to expel the French from the Ohio Land. The French and their Indian allies ambushed the trek, mowing downward over 900 casualties including the mortally wounded Braddock. During what became known as the Battle of the Monongahela, British troops retreated in disarray but Washington rode back and forth across the battlefield, rallying the remnants of the British and Virginian forces to an organized retreat.[11] [12]

Commander of Virginia Regiment [edit]

Governor Dinwiddie rewarded Washington in 1755 with a commission every bit "Colonel of the Virginia Regiment and Commander in Primary of all forces now raised in the defense of His Majesty's Colony" and gave him the task of defending Virginia's frontier. The Virginia Regiment was the first full-time American military unit in the colonies (every bit opposed to part-time militias and the British regular units). Washington was ordered to "deed defensively or offensively" equally he thought all-time.[thirteen] In command of a thousand soldiers, Washington was a authoritarian who emphasized training. He led his men in barbarous campaigns against the Indians in the west; in 10 months units of his regiment fought 20 battles, and lost a third of its men. Washington's strenuous efforts meant that Virginia'south borderland population suffered less than that of other colonies; Ellis concludes "it was his only unqualified success" in the war.[fourteen] [fifteen]

In 1758, Washington participated in the Forbes Expedition to capture Fort Duquesne. He was embarrassed by a friendly burn down episode in which his unit of measurement and some other British unit thought the other was the French enemy and opened fire, with xiv expressionless and 26 wounded in the mishap. In the end there was no real fighting for the French abandoned the fort and the British scored a major strategic victory, gaining control of the Ohio Valley. Upon his return to Virginia, Washington resigned his commission in December 1758, and did not return to military life until the outbreak of the revolution in 1775.[16]

Although Washington never gained the commission in the British army he yearned for, in these years he gained valuable military, political, and leadership skills,[17] and received significant public exposure in the colonies and abroad.[nine] [18] He closely observed British military tactics, gaining a keen insight into their strengths and weaknesses that proved invaluable during the Revolution. He demonstrated his toughness and courage in the most difficult situations, including disasters and retreats. He developed a command presence—given his size, forcefulness, stamina, and bravery in battle, he appeared to soldiers to be a natural leader and they followed him without question.[19] [xx] Washington learned to organize, train, and drill, and subject field his companies and regiments. From his observations, readings and conversations with professional officers, he learned the basics of battleground tactics, likewise as a expert understanding of problems of organization and logistics.[21] He developed a very negative idea of the value of militia, who seemed too unreliable, besides undisciplined, and too brusque-term compared to regulars.[22] On the other hand, his experience was limited to command of about 1,000 men, and came but in remote frontier atmospheric condition.[23]

Lessons learned [edit]

Washington never gained the commission in the British army that he yearned for, but in these years he gained valuable military, political, and leadership skills,[24] closely observing their tactics, gaining a keen insight into their strengths and weaknesses that proved invaluable during the Revolution. He learned the nuts of battlefield tactics from his observations, readings, and conversations with professional officers, as well as a good understanding of problems of organization and logistics.[25] He gained an understanding of overall strategy, especially in locating strategic geographical points.[26]

Washington demonstrated his resourcefulness and courage in the most difficult situations, including disasters and retreats. He developed a command presence, given his size, strength, stamina, and bravery in boxing, which demonstrated to soldiers that he was a natural leader whom they could follow without question.[27] Washington'due south fortitude in his early years was sometimes manifested in less constructive means. Biographer John R. Alden contends that Washington offered "fulsome and insincere flattery to British generals in vain attempts to win great favor" and on occasion showed youthful airs, every bit well as jealousy and ingratitude in the midst of impatience.[28]

American Revolutionary War service [edit]

As political tensions rose in the colonies, Washington in June 1774 chaired the meeting at which the "Fairfax Resolves" were adopted, which chosen for, among other things, the convening of a Continental Congress. In August, Washington attended the Start Virginia Convention, where he was selected equally a delegate to the First Continental Congress.[29] As tensions rose further in 1774, he assisted in the preparation of county militias in Virginia and organized enforcement of the cold-shoulder of British appurtenances instituted past the Congress.[30] [31]

Boston [edit]

After the Battles of Lexington and Concord near Boston in April 1775, the colonies went to war. Washington appeared at the Second Continental Congress in a military machine uniform, signaling that he was prepared for war.[32] Congress created the Continental Army on June xiv, 1775. He was nominated past John Adams of Massachusetts, who chose him in part because he was a Virginian and would thus draw the southern colonies into the conflict.[33] [34] [35] Congress appointed George Washington "General & Commander in main of the regular army of the United Colonies and of all the forces raised or to be raised by them", and instructed him on June 22, 1775, to have charge of the siege of Boston.[36]

Washington causeless control of the colonial forces exterior Boston on July iii, 1775 (coincidentally making July iv his first full twenty-four hours as commander-in-chief), during the ongoing siege of Boston. His beginning steps were to found procedures and to way what had begun every bit militia regiments into an constructive fighting force.[37]

When inventory returns exposed a dangerous shortage of gunpowder, Washington asked for new sources. British arsenals were raided (including some in the Westward Indies) and some manufacturing was attempted; a barely adequate supply (about 2.five million pounds) was obtained by the end of 1776, mostly from France.[38] In search of heavy weapons, he sent Henry Knox on an expedition to Fort Ticonderoga to call up cannons that had been captured there.[39] He resisted repeated calls from Congress to launch attacks against the British in Boston, calling war councils that supported the decisions confronting such action.[40] Before the Continental Navy was established in November 1775 he, without Congressional authorization, began arming a "secret navy" to prey on poorly protected British transports and supply ships.[41] When Congress authorized an invasion of Quebec,[42] Washington authorized Benedict Arnold to lead a force from Cambridge to Quebec City through the wilderness of nowadays-day Maine.[43]

As the siege dragged on, the affair of expiring enlistments became a matter of serious concern.[44] Washington tried to convince Congress that enlistments longer than 1 year were necessary to build an constructive fighting forcefulness, but he was rebuffed in this effort. The 1776 institution of the Continental Army only had enlistment terms of one year, a matter that would once more exist a problem in belatedly 1776.[45] [46]

Washington finally forced the British to withdraw from Boston by putting Henry Knox's artillery on Dorchester Heights overlooking the city, and preparing in detail to attack the metropolis from Cambridge if the British tried to assault the position.[47] The British evacuated Boston and sailed away, although Washington did not know they were headed for Halifax, Nova Scotia.[48] Assertive they were headed for New York City (which was indeed Major General William Howe'south eventual destination), Washington rushed well-nigh of the army there.[49]

Defeated at New York City [edit]

Washington's success in Boston was non repeated in New York. Recognizing the city's importance as a naval base of operations and gateway to the Hudson River, he delegated the task of fortifying New York to Charles Lee in February 1776.[50] Despite the city'south poor defensibility, Congress insisted that Washington defend it. The faltering military machine campaign in Quebec also led to calls for additional troops there, and Washington detached six regiments due north nether John Sullivan in April.[51]

Washington had to deal with his offset major command controversy while in New York, which was partially a product of regional friction. New England troops serving in northern New York nether General Philip Schuyler, a scion of an onetime patroon family of New York, objected to his aristocratic style, and their Congressional representatives lobbied Washington to supersede Schuyler with Horatio Gates. Washington tried to quash the issue by giving Gates command of the forces in Quebec, but the collapse of the Quebec expedition brought renewed complaints.[52] Despite Gates' experience, Washington personally preferred Schuyler, and put Gates in a part subordinate to Schuyler. The episode exposed Washington to Gates' want for advancement, possibly at his expense, and to the latter'southward influence in Congress.[53]

General Howe'due south ground forces, reinforced past thousands of boosted troops from Europe and a armada under the command of his brother, Admiral Richard Howe, began arriving off New York in early on July, and fabricated an unopposed landing on Staten Island.[54] Without intelligence most Howe'south intentions, Washington was forced to split up his still poorly trained forces, principally between Manhattan and Long Island.[55]

Washington leads the retreat from Long Island

In August, the British finally launched their campaign to capture New York City. They offset landed on Long Island in forcefulness, and flanked Washington's forwards positions in the Boxing of Long Island. Howe refused to act on a significant tactical advantage that could take resulted in the capture of the remaining Continental troops on Long Island, merely he chose instead to congregate their positions.[56] In the confront of a siege he seemed certain to lose, Washington then decided to withdraw. In what some historians call ane of his greatest military machine feats, executed a nighttime withdrawal from Long Island across the E River to Manhattan to save those troops.[57]

The Howe brothers then paused to consolidate their position, and the admiral engaged in a fruitless peace conference with Congressional representatives on September 11. Four days later the British landed on Manhattan, scattering inexperienced militia into a panicked retreat, and forcing Washington to retreat further.[57] After Washington stopped the British advance up Manhattan at Harlem Heights on September 16, Howe once more fabricated a flanking maneuver, landing troops at Pell's Point in a bid to cut off Washington's artery of retreat. To defend confronting this move, Washington withdrew most of his army to White Plains, where after a short boxing on October 28 he retreated further due north. This isolated the remaining Continental Army troops in upper Manhattan, so Howe returned to Manhattan and captured Fort Washington in mid November, taking about iii,000 prisoners. Four days later, Fort Lee, across the Hudson River from Fort Washington, was besides taken. Washington brought much of his regular army beyond the Hudson into New Jersey, but was immediately forced to retreat past the ambitious British advance.[58] During the campaign a general lack of organization, shortages of supplies, fatigue, sickness, and above all, lack of confidence in the American leadership resulted in a melting away of untrained regulars and frightened militia. Washington grumbled, "The laurels of making a brave defence does non seem to be sufficient stimulus, when the success is very hundred-to-one, and the falling into the Enemy'due south easily probable."[59]

Counterattack in New Jersey [edit]

Afterward the loss of New York, Washington's army was in two pieces. Ane detachment remained north of New York to protect the Hudson River corridor, while Washington retreated beyond New Bailiwick of jersey into Pennsylvania, chased past General Charles, Earl Cornwallis.[60] Spirits were low, popular back up was wavering, and Congress had abased Philadelphia, fearing a British assail.[61] Washington ordered Full general Gates to bring troops from Fort Ticonderoga, and as well ordered General Lee's troops, which he had left n of New York City, to join him.[62]

Despite the loss of troops due to desertion and expiring enlistments, Washington was heartened by a rise in militia enlistments in New Jersey and Pennsylvania.[63] These militia companies were agile in circumscribing the furthest outposts of the British, limiting their ability to scout and forage.[64] Although Washington did not coordinate this resistance, he took advantage of information technology to organize an assail on an outpost of Hessians in Trenton.[65] On the night of Dec 25–26, 1776, Washington led his forces across the Delaware River and surprised the Hessian garrison the following morning, capturing 1,000 Hessians.[66]

This activity significantly boosted the army'due south morale, merely information technology likewise brought Cornwallis out of New York. He reassembled an army of more than 6,000 men, and marched most of them against a position Washington had taken due south of Trenton. Leaving a garrison of i,200 at Princeton, Cornwallis so attacked Washington's position on Jan 2, 1777, and was three times repulsed earlier darkness set in.[67] During the night Washington evacuated the position, masking his army'southward movements past instructing the camp guards to maintain the appearance of a much larger force.[68] Washington then circled around Cornwallis's position with the intention of attacking the Princeton garrison.[69]

On January 3, Hugh Mercer, leading the American advance baby-sit, encountered British soldiers from Princeton under the control of Charles Mawhood. The British troops engaged Mercer and in the ensuing battle, Mercer was mortally wounded. Washington sent reinforcements under General John Cadwalader, which were successful in driving Mawhood and the British from Princeton, with many of them fleeing to Cornwallis in Trenton. The British lost more than one quarter of their force in the battle, and American morale rose with the great victory.[70]

These unexpected victories drove the British back to the New York City area, and gave a dramatic boost to Revolutionary morale.[71] During the wintertime, Washington, based in winter quarters at Morristown, New Jersey, loosely coordinated a low-level militia war against British positions in New Bailiwick of jersey, combining the actions of New Jersey and Pennsylvania militia companies with careful utilize of Continental Ground forces resources to harry and harass the British and German troops quartered in New Jersey.[72]

Washington's mixed performance in the 1776 campaigns had not led to significant criticism in Congress.[73] Before fleeing Philadelphia for Baltimore in December, Congress granted Washington powers that have always since been described equally "dictatorial".[74] The successes in New Jersey well-nigh deified Washington in the optics of some Congressmen, and the body became much more deferential to him as a effect.[75] Washington'south performance also received international find: Frederick the Great, one of the greatest military minds, wrote that "the achievements of Washington [at Trenton and Princeton] were the about vivid of whatever recorded in the history of war machine achievements."[76]

Loss of Philadelphia [edit]

In May 1777, the British resumed military operations, with General Howe attempting without success to draw Washington from his defensive position in New Jersey'southward Watchung Mountains, while General John Burgoyne led an army due south from Quebec toward Albany, New York.[77] Following Burgoyne'due south capture of Fort Ticonderoga without resistance in early July, General Howe boarded a large part of his army on transports and sailed off, leaving Washington mystified as to his destination.[78] [79] Washington dispatched some of his troops north to help in Albany's defense, and moved most of the rest his forces southward of Philadelphia when it became articulate that was Howe's target.[80]

Congress, at the urging of its diplomatic representatives in Europe, had also issued military machine commissions to a number of European soldiers of fortune in early on 1777. Two of those recommended past Silas Deane, the Marquis de Lafayette and Thomas Conway, would prove to be important in Washington'southward activities.[81] [82] Lafayette, just xx years old, was at kickoff told that Deane had exceeded his authority in offering him a major full general's commission, but offered to volunteer in the army at his own expense.[83] Washington and Lafayette took an instant liking to one another when they met, and Lafayette became one of Washington's most trusted generals and confidants.[84] Conway, on the other hand, did non call up highly of Washington's leadership, and proved to be a source of problem in the 1777 entrada flavour and its aftermath.[85]

Full general Howe landed his troops south of Philadelphia at the northern end of Chesapeake Bay, and turned Washington'due south flank at the Boxing of Brandywine on September 11, 1777. Afterwards further maneuvers, Washington was forced to retreat away from the city, allowing British troops to march unopposed into Philadelphia on September 26. Washington's failure to defend the capital brought on a tempest of criticism from Congress, which fled the city for York, and from other army officers. In part to silence his critics, Washington planned an elaborate assault on an exposed British base in Germantown.[86] [87] The October 4 Battle of Germantown failed in office due to the complication of the assault, and the inexperience of the militia forces employed in information technology.[88] Over 400 of Washington's troops were captured, including Colonel George Mathews and the entire 9th Virginia Regiment.[89] Information technology did not help that Adam Stephen, leading one of the branches of the attack, was drunk, and bankrupt from the agreed-upon plan of attack.[88] He was court martialed and cashiered from the army. Historian Robert Leckie observes that the battle was a near thing, and that a small number of changes might have resulted in a decisive victory for Washington.[90]

Washington'south strategic decisions in the summer of 1777 greatly assisted Gates' ground forces at Saratoga at the toll of his own campaign in the Philadelphia vicinity because he thought Howe would travel northward to Saratoga and not southward to Philadelphia. He took a major risk in July by detaching over a thousand soldiers from his own army to travel n to bring together the Saratoga campaign. He sent aid north in the grade of Major Full general Benedict Arnold, his most aggressive field commander, and Major Full general Benjamin Lincoln, a Massachusetts man noted for his influence with the New England militia and also one of Washington'due south most favorite generals.[91] He ordered 750 men from Israel Putnam'south forces defending the New York highlands to join Gates' regular army. He besides sent some of the all-time forces from his own army: Colonel Daniel Morgan and the newly formed Provisional Rifle Corps, which comprised about 500 specially selected riflemen from Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia, called for their sharpshooting ability.[92] This unit came to be known every bit Morgan's Riflemen.

Meanwhile, Burgoyne, out of accomplish from assist from Howe, was trapped and forced to surrender his entire ground forces on Oct 17, x days after the Battle of Bemis Heights.[93] The victory made a hero of Full general Gates, who received the applause of Congress.[94] While this was taking place Washington presided from a altitude over the loss of control of the Delaware River to the British, and marched his army to its wintertime quarters at Valley Forge in December.[95] Washington chose Valley Forge, over recommendations that he army camp either closer or further from Philadelphia, because it was close enough to monitor British army movements, and protected rich farmlands to the w from the enemy's foraging expeditions.[96]

Valley Forge [edit]

Washington'due south regular army stayed at Valley Forge for the side by side vi months.[97] Over the winter, approximately ii,500–3,000 out of 11,000 men died (although estimates vary) from illness and exposure. The army's difficulties were exacerbated by a number of factors, including a quartermaster'due south department that had been desperately mismanaged by i of Washington's political opponents, Thomas Mifflin, and the preference of farmers and merchants to sell their goods to the British, who paid in sterling silvery currency instead of the almost worthless Continental paper currency.[98] [99] Profiteers as well sought to benefit at the regular army's expense, charging it 1,000 times what they charged civilians for the same goods. Congress authorized Washington to seize supplies needed for the army, but he was reluctant to use such authority, since it smacked of the tyranny the war was supposedly being fought over.[98]

During the winter he introduced a full-scale training program supervised by Baron von Steuben, a veteran of the Prussian full general staff. Despite the hardships the army suffered, this program was a remarkable success, and Washington's army emerged in the spring of 1778 a much more than disciplined force.[100]

Washington himself had to face up discontent at his leadership from a variety of sources. His loss of Philadelphia prompted some members of Congress to discuss removing him from control.[101] They were prodded forth by Washington's detractors in the military, who included Generals Gates, Mifflin, and Conway.[102] Gates in item was viewed by Conway and Congressmen Benjamin Rush and Richard Henry Lee as a desirable replacement for Washington.[103] [104] Although there is no evidence of a formal conspiracy, the episode is known as the Conway Cabal because the scale of the discontent within the ground forces was exposed past a disquisitional letter of the alphabet from Conway to Gates, some of whose contents were relayed to Washington.[105] Washington exposed the criticisms to Congress, and his supporters, within Congress and the army, rallied to support him.[106] Gates eventually apologized for his function in the affair, and Conway resigned.[107] [108] Washington's position and say-so were not seriously challenged over again. Biographer Ron Chernow points out that Washington'due south handling of the episode demonstrated that he was "a consummate political infighter" who maintained his temper and nobility while his opponents schemed.[102]

French entry into the war [edit]

The victory at Saratoga (and to some extent Washington'southward almost success at Germantown) were influential in convincing French republic to enter the state of war openly every bit an American ally. French entry into the war changed its dynamics, for the British were no longer sure of command of the seas and had to worry almost an invasion of their dwelling islands and other colonial territories across the earth. The British, now under the command of General Sir Henry Clinton, evacuated Philadelphia in 1778 and returned to New York Urban center, with Washington attacking them along the way at the Boxing of Monmouth; this was the last major boxing in the north. Prior to the battle Washington gave command of the advance forces to Charles Lee, who had been exchanged earlier in the year. Lee, despite business firm instructions from Washington, refused Lafayette's proposition to launch an organized attack on the British rear, and and then retreated when the British turned to face him. When Washington arrived at the head of the main army, he and Lee had an angry exchange of words, and Washington ordered Lee off the command. Washington, with his army's tactics and ability to execute improved by the training programs of the previous wintertime, was able to recover, and fought the British to a depict. Lee was court martialed and eventually dismissed from the ground forces.[109]

The war in the north was finer stalemated for the next few years. The British successfully defended Newport, Rhode Island against a Franco-American invasion attempt that was frustrated by bad weather and difficulties in cooperation between the allies.[110] [111] British and Indian forces organized and supported by Sir Frederick Haldimand in Quebec began to raid frontier settlements in 1778, and Savannah, Georgia was captured belatedly in the year.[112] In response to the borderland activeness Washington organised a major expedition against the Iroquois in the summertime of 1779. In the Sullivan Expedition, a sizable force under Major Full general John Sullivan collection the Iroquois from their lands in northwestern New York in reprisal for the frontier raids.[113] [114]

Washington's opponent in New York was also active. Clinton engaged in a number of amphibious raids against littoral communities from Connecticut to Chesapeake Bay, and probed at Washington's defenses in the Hudson River valley.[115] Coming up the river in force, he captured the primal outpost of Stony Signal, but avant-garde no further. When Clinton weakened the garrison there to provide men for raiding expeditions, Washington organized a counterstrike. Full general Anthony Wayne led a force that, solely using the bayonet, recaptured Stony Point.[116] The Americans chose not to hold the postal service, but the operation was a boost to American morale and a blow to British morale. American morale was dealt a blow later in the twelvemonth, when the second major endeavor at Franco-American cooperation, an try to retake Savannah, failed with heavy casualties.[117]

Difficult times [edit]

The winter of 1779–80 was one of the coldest in recorded colonial history. New York Harbor froze over, and the winter camps of the Continental Army were deluged with snowfall, resulting in hardships exceeding those experienced at Valley Forge.[118] The war was declining in popularity, and the inflationary issuance of paper currency by Congress and the states akin harmed the economic system, and the ability to provision the ground forces. The paper currency also hit the ground forces's morale, since information technology was how the troops were paid.[119]

The British in late 1779 embarked on a new strategy based on the assumption that nearly Southerners were Loyalists at heart. General Clinton withdrew the British garrison from Newport, and marshalled a force of more than x,000 men that in the showtime half of 1780 successfully besieged Charleston, South Carolina. In June 1780 he captured over 5,000 Continental soldiers and militia in the single worst defeat of the war for the Americans.[120] Washington had at the end of March pessimistically dispatched several regiments troops southward from his army, hoping they might take some effect in what he saw as a looming disaster.[121]

Washington's army suffered from numerous problems in 1780: it was undermanned, underfunded, and underequipped.[122] Because of these shortcomings Washington resisted calls for major expeditions, preferring to remain focused on the principal British presence in New York. Knowledge of discontent within the ranks in New Jersey prompted the British in New York to make two attempts to attain the principal army base of operations at Morristown. These attempts were defeated, with pregnant militia support, in battles at Connecticut Farms and Springfield.[123]

September 1780 brought a new shock to Washington. British Major John André had been arrested outside New York, and papers he carried exposed a conspiracy between the British and General Benedict Arnold.[124] Washington respected Arnold for his military skills, and had, after Arnold'southward severe injuries in the Battles of Saratoga in Oct 1777, given him the military control of Philadelphia.[125] During his administration at that place, Arnold had made many political enemies, and in 1779 he began secret negotiations with General Clinton (mediated in part by André) that culminated in a plot to give up W Bespeak, a command Arnold requested and Washington gave him in July 1780.[126] Arnold was alerted to André's abort and fled to the British lines shortly before Washington's arrival at Due west Point for a meeting.[127] In negotiations with Clinton, Washington offered to exchange André for Arnold, but Clinton refused. André was hanged as a spy, and Arnold became a brigadier full general in the British Regular army.[128] Washington organized an attempt to kidnap Arnold from New York City; it was frustrated when Arnold was sent on a raiding expedition to Virginia.[129]

Espionage [edit]

Washington was successful in developing an espionage network, which kept runway of the British and loyalist forces while misleading the enemy as to the forcefulness of the American and French positions, and their intentions. British intelligence, by contrast, was poorly done. Many prominent loyalists had fled to London, where they convinced Lord Jermaine and other pinnacle officials that in that location was a big potential loyalist fighting force that would rise up and join the British as soon as they were in the vicinity. This was entirely false, only the British relied upon it heavily, peculiarly in the southern campaigns of 1780–81, leading to their disasters. Washington deceived the British in New York City marching his entire army, the unabridged French Army, effectually the city all the way to Virginia, where they surprised Cornwallis and his army.[130] The greatest failure of British intelligence was the misunderstanding between the senior command in London, and New York regarding the need to support Burgoyne's invasion of New York. British communication failures and lack of intelligence on what was happening led to the surrender of Burgoyne'southward entire army.[131]

Washington used systematic reconnaissance on enemy positions past scouts and sponsored Major Benjamin Tallmadge who prepare the Culper spy ring. Washington distrusted double agents, and was fooled by Benedict Arnold's treachery.[132] Washington paid close attending to espionage reports, and acted on them. He made sure his intelligence officers briefed one another; he did not insist on prior approval of their plans. His intelligence system became an essential arm in molding the Americans partisan fashion asymmetrical strategy. This laid the groundwork in the 1790s for Washington to codify intelligence gathering as an important tool in presidential power.[133]

Victory [edit]

Delineation by John Trumbull of the surrender of Lord Cornwallis's army at Yorktown

A British ground forces under General Cornwallis, fighting its mode through the Carolinas and Virginia, fabricated its style to Yorktown to be evacuated by the British Navy. Washington coordinated an elaborate performance whereby both the French army in New England and the American Army in New York slipped off to Virginia without the British noticing. Cornwallis found himself surrounded, and a French naval victory against the British rescue fleet dashed his hopes. The give up of Cornwallis to Washington on October 17, 1781, marked the finish of serious fighting.[134] In London, the war party lost control of parliament, and the British negotiated the Treaty of Paris (1783) That ended the state of war. Hoping to proceeds the United states as a major trading partner, the British offered surprisingly generous terms.

Washington designed the American strategy for victory. It enabled Continental forces to maintain their strength for half-dozen years and to capture ii major British armies at Saratoga in 1777 and Yorktown in 1781. Some historians accept lauded Washington for the selection and supervision of his generals, preservation and command of the army, coordination with the Congress, with state governors and their militia, and attention to supplies, logistics, and preparation, and although Washington was repeatedly outmaneuvered by British generals, his overall strategy proved to be successful: keep control of 90% of the population at all times (including suppression of the Loyalist civilian population); keep the army intact; avoid decisive battles; and look for an opportunity to capture an outnumbered enemy army. Washington was a armed forces conservative: he preferred building a regular army on the European model and fighting a conventional war, and often complained about the undisciplined American militia.[135] [136] [137]

Resignation [edit]

I of Washington's about important contributions as commander-in-principal was to found the precedent that civilian-elected officials, rather than military officers, possessed ultimate authority over the military. This was a key principle of Republicanism, but could easily have been violated by Washington. Throughout the state of war, he deferred to the authority of Congress and state officials, and he relinquished his considerable military ability in one case the fighting was over. In March 1783, Washington used his influence to disperse a grouping of Regular army officers who had threatened to face up Congress regarding their back pay. Washington disbanded his army and appear his intent to resign from public life in his "Adieu Orders to the Armies of the U.s.." A few days subsequently, on Nov 25, 1783, the British evacuated New York Urban center, and Washington and the governor took possession of the metropolis; at Fraunces Tavern in the city on December iv, he formally bade his officers farewell. On December 23, 1783, Washington resigned his commission as commander-in-chief to the Congress of the Confederation at Annapolis, Maryland.[138]

Quasi-War service [edit]

In the fall of 1798, Washington became immersed in the business organisation of creating a military force to deal with the threat of an all-out war with France. President John Adams asked him to resume the mail service of commander-in-chief and to heighten an ground forces in the outcome war broke out. Washington agreed, stipulating that he would merely serve in the field if it became absolutely necessary, and if he could choose his subordinates.[139] Disputes arose over the relative rankings of his called control. Washington selected Alexander Hamilton as his inspector general and second in command, followed past Charles Cotesworth Pinckney and Henry Knox. This hierarchy was an inversion of the ranks these men had held during the revolution. Adams wanted to contrary the order, giving Knox the most important role, but Washington was insistent, threatening to resign if his choices were not approved.[140] He prevailed, but the episode noticeably cooled his relationship with Henry Knox, and impaired Adams' relations with his cabinet.[141] The resolution of this affair brought no opportunity for balance: Washington engaged in the slow task of finding officers for the new military machine formations. In the jump of 1799, the relaxation of tensions between French republic and the United States allowed Washington to redirect his attention to his personal affairs.[142]

Posthumous promotion [edit]

George Washington died on December fourteen, 1799, at the age of 67. Upon his passing he was listed as a retired lieutenant full general on the rolls of the Us Army. Over the next 177 years, diverse officers surpassed Washington in rank, including most notably John J. Pershing, who was promoted to General of the Armies for his role in Earth State of war I. With upshot from four July 1976, Washington was posthumously promoted to the same rank by dominance of a congressional articulation resolution.[143] The resolution stated that Washington'due south seniority had rank and precedence over all other grades of the Armed Forces, past or nowadays, effectively making Washington the highest ranked U.Due south. officer of all fourth dimension.[144]

Historical evaluations [edit]

Historians fence whether Washington preferred to fight major battles or to utilize a Fabian strategy[a] to harass the British with quick, abrupt attacks followed by a retreat so that the larger British ground forces could non grab him.[b] His southern commander Greene did utilise Fabian tactics in 1780–81; Washington did then only in fall 1776 to spring 1777, after losing New York Metropolis and seeing much of his regular army cook abroad. Trenton and Princeton were Fabian's examples. By summer 1777 Washington had rebuilt his strength and his conviction; he stopped using raids and went for large-calibration confrontations, equally at Brandywine, Germantown, Monmouth, and Yorktown.[146]

Rank history [edit]

| Rank | Organization | Engagement |

|---|---|---|

| Major and Adjutant | Province of Virginia militia | Dec 13, 1752[147] |

| Lieutenant Colonel | Virginia Regiment | March 15, 1754[148] |

| Colonel | Virginia Regiment | August 14, 1755[149] |

| | Continental Regular army | June 15, 1775 |

| | United States Regular army | July 3, 1798 |

| Full general of the Armies of the United States (posthumous) | United States Army | 13 March 1978, retrospective to July 4, 1976[150] |

- While serving as a General, Washington wore 3 six-pointed stars (iii five-pointed stars are now used as the insignia of a lieutenant general).[151]

Summaries of Washington's Revolutionary State of war battles [edit]

The following are summaries of battles where George Washington was the commanding officer.

| Boxing | Appointment | Consequence | Opponent | American troop strength | British troop strength | American casualties | British casualties | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boston | July three, 1775 – March 17, 1776 | Victory | Gage and Howe | half dozen,000–sixteen,000 | 4,000–11,000 | 19 | 95 | |

| Long Island | August 27, 1776 | Defeat | Howe | 10,000 | xx,000 | 2,000 | 388 | |

| Kip's Bay | September xv, 1776 | Defeat | Clinton | 500 | 4,000 | 370 | 12 | |

| Harlem Heights | September sixteen, 1776 | Victory | Leslie | 1,800 | 5,000 | 130 | 92–390 | Washington'southward starting time battlefield victory of the war. |

| White Plains | Oct 28, 1776 | Defeat | Howe | 3,100 | iv,000–7,500 | 217 | 233 | |

| Fort Washington | November 16, 1776 | Defeat | Howe | iii,000 | eight,000 | 2,992 | 458 | |

| Trenton | Dec 26, 1776 | Victory | Rall | two,400 | one,500 | 5 | 905–ane,005 | |

| 2nd Trenton | January 2, 1777 | Victory | Cornwallis | half dozen,000 | 5,000 | 7–100 | 55–365 | |

| Princeton | Jan 3, 1777 | Victory | Mawhood | 4,500 | one,200 | 65–89 | 270–450 | |

| Brandywine | September xi, 1777 | Defeat | Howe | 14,600 | 15,500 | 1,300 | 587 | |

| Germantown | October 4, 1777 | Defeat | Howe | 11,000 | 9,000 | 1,111 | 533 | |

| White Marsh | December 5–8, 1777 | Inconclusive | Howe | nine,500 | 10,000 | 204 | 112 | |

| Monmouth | June 28, 1778 | Inconclusive | Clinton | 11,000 | 14,000–xv,000 | 362–500 | 295–1,136 | |

| Yorktown | September 28 – October 19, 1781 | Victory | Cornwallis | xviii,900 | 9,000 | 389 | vii,884–8,589 |

See also [edit]

- List of The states militia units in the American Revolutionary War

- Bibliography of George Washington

- Listing of George Washington manufactures

Notes [edit]

- ^ The term comes from the Roman strategy used past Full general Fabius against Hannibal's invasion in the Second Punic State of war.

- ^ Ferling, and Ellis contend that Washington favored Fabian tactics, and Higginbotham denies it.[145]

References [edit]

- ^ Anderson (2000), p. 30

- ^ Freeman, p. 1:268

- ^ Freeman, pp. 1:274–327

- ^ Lengel, pp. 23–24

- ^ Lengel, pp. 31–38

- ^ Grizzard, pp. 115–119

- ^ Ellis, pp. 17–eighteen

- ^ The governor promised land bounties to the soldiers and officers who volunteered in 1754; Virginia finally made good on the promise in the early 1770s, with Washington receiving championship to 23,200 acres near where the Kanawha River flows into the Ohio River, in what is now western West Virginia. Grizzard, pp. 135–137

- ^ a b Ellis, p. 14

- ^ Anderson (2005), p. 56

- ^ Ellis, p. 22

- ^ "The Boxing of the Monongahela". World Digital Library. 1755. Retrieved 2013-08-03 .

- ^ Flexner, George Washington: the Forge of Experience, 1732–1775 (1965), p. 138

- ^ Fischer, pp. 15–16

- ^ Ellis, p. 38

- ^ Lengel, pp. 75–76, 81

- ^ Chernow, ch. eight; Freeman and Harwell, pp. 135–139; Flexner (1984), pp. 32–36; Ellis, ch. 1; Higginbotham (1985), ch. i

- ^ O'Meara, p. 45

- ^ Ellis, pp. 38,69

- ^ Fischer, p. thirteen

- ^ Higginbotham (1985), pp. xiv–fifteen

- ^ Higginbotham (1985), pp. 22–25

- ^ Freeman and Harwell, pp. 136–137

- ^ Chernow 2010, pp. 91–93.

- ^ Higginbotham 1985, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Lengel 2005, p. 80.

- ^ Ellis 2004; Fischer 2004, p. 13.

- ^ Alden 1993, p. lxx.

- ^ Ferling (1998), p. 99

- ^ Lengel, p. 84

- ^ Ferling (1998), p. 108

- ^ Lengel, p. 86

- ^ Bell (1983), p. 52

- ^ Ferling (2010), p. 85

- ^ Lengel, pp. 87–88

- ^ "Instructions from the Continental Congress". Founders Online. National Archives. Retrieved January x, 2020.

- ^ Lengel, pp. 105–109

- ^ Stephenson, Orlando Westward (January 1925). "The Supply of Gunpowder in 1776". American Historical Review. 30 (2): 271–281. doi:ten.2307/1836657. JSTOR 1836657.

- ^ McCullough, p. 84

- ^ McCullough, pp. 53, 86

- ^ Nelson, p. 86

- ^ Ferling (2010), p. 94

- ^ Lengel, p. 113

- ^ Lengel, p. 114

- ^ Ferling (2010), p. 98

- ^ Lengel, p. 175

- ^ Flexner (1968), pp. 73–75

- ^ McCullough, pp. 91–105

- ^ Schecter, pp. 67–90

- ^ Lengel, p. 179

- ^ Johnston, p. 63

- ^ Flexner (1968), p. 99

- ^ Flexner (1968), p. 100

- ^ Fischer, p. 34

- ^ Fischer, pp. 83–89

- ^ Fischer, pp. 89–102

- ^ a b Fischer, pp. 102–107

- ^ Fischer, pp. 107–125

- ^ Fischer, p. 101

- ^ Schecter, pp. 259–263

- ^ Fischer, pp. 138–142

- ^ Fischer, p. 150

- ^ Fischer, pp. 196–200

- ^ Ketchum, pp. 228–230

- ^ Fischer, p. 201

- ^ Ketchum pp. 250–275

- ^ Fischer, pp. 209–307

- ^ Ketchum p. 294

- ^ Schecter, p. 267

- ^ Schecter, p. 268

- ^ Leckie, pp. 333–335

- ^ Fischer, pp. 354–382

- ^ Ferling (2010), p. 125

- ^ Ketchum, p. 211

- ^ Ferling (2010), p. 126

- ^ Leckie, p. 333

- ^ Leckie, pp. 344–346

- ^ Leckie, p. 346

- ^ Ferling (2010), p. 128

- ^ Leckie, p. 348

- ^ Leckie, p. 341

- ^ Ferling (2010), p. 149

- ^ Leckie, pp. 342–343

- ^ Lengel, p. xxix

- ^ Lengel, pp. xxii, xxv

- ^ Leckie, pp. 356–358

- ^ Lengel, p. 253

- ^ a b Leckie, p. 359–363

- ^ Jenkins, Charles F. (1904) The Guide Volume to Historic Germantown, Innes & Sons, 1904. Jenkins, Charles F. The Guide Book to Historic Germantown, Innes & Sons, 1904. p 142.

- ^ Leckie, p. 365

- ^ Nickerson (1967), p. 180

- ^ Nickerson (1967), p. 216

- ^ Leckie, pp. 414–416

- ^ Lengel, p. 277

- ^ Lengel, pp. 263–267

- ^ Leckie, p. 434

- ^ Leckie, pp. 435, 469

- ^ a b Leckie, p. 435

- ^ Fleming, pp. 89–91

- ^ Leckie, pp. 438–444

- ^ Chernow, p. 316

- ^ a b Chernow, p. 320

- ^ Fleming, pp. 93–97, 121

- ^ Leckie, p. 450

- ^ Leckie, pp. 445–449

- ^ Chernow, pp. 317–320

- ^ Fleming, p. 202

- ^ Leckie, p. 451

- ^ Leckie, pp. 467–489

- ^ Freeman, pp. v:50–52

- ^ Leckie, p. 492

- ^ Leckie, pp. 492–493

- ^ Ferling (2010), pp. 194–195

- ^ Leckie, pp. 493–495

- ^ Ferling (2010), p. 196

- ^ Leckie, p. 502

- ^ Leckie, pp. 503–504

- ^ Leckie, p. 504

- ^ Leckie, p. 505

- ^ Leckie, pp. 496, 507–517

- ^ Freeman, p. 5:155

- ^ Freeman, pp. 5:152–155

- ^ Freeman, pp. v:169–173

- ^ Freeman, pp. 5:196–295

- ^ Chernow, p. 338

- ^ Leckie, pp. 549–569

- ^ Chernow, p. 382

- ^ Leckie, pp. 578–581

- ^ Chernow, p. 387

- ^ George J.A. O'Toole, Honorable Treachery: A History of US Intelligence, Espionage, and Covert Action from the American Revolution to the CIA (2014) ch 1–5.

- ^ Jared B. Harty, "George Washington: Spymaster and General Who Saved the American Revolution" (Staff paper No. ATZL-SWV. Army Command And Full general Staff College Fort Leavenworth, Schoolhouse Of Advanced War machine Studies, 2012) online.

- ^ Edward Lengel, "Patriots Under Cover." American History 51.2 (2016): 26+.

- ^ Sean Halverson, "Unsafe Patriots: Washington'due south Hidden Army during the American Revolution." Intelligence and National Security 25.ii (2010): 123–146.

- ^ Robert A. Selig, "Washington, Rochambeau, and the Yorktown Entrada of 1781." in Edward G. Lengel, ed. A Companion to George Washington, (2012) pp: 266–287.

- ^ Thomas A. Rider, "George Washington: America's Showtime Soldier," in Edward K. Lengel, ed. A Companion to George Washington, (2012) pp: 378–98

- ^ Stephen Brumwell, George Washington: Gentleman Warrior (2013)

- ^ Andrew J. O'Shaughnessy, "Military Genius?: The Generalship of George Washington," Reviews in American History (2014) 42#3 pp. 405–410 online

- ^ William 1000. Fowler Jr, American crunch: George Washington and the dangerous 2 years afterwards Yorktown, 1781–1783 (2011)

- ^ Lengel, p. 360

- ^ Lengel, pp. 360–362

- ^ Lengel, p. 362

- ^ Lengel, p. 363

- ^ Public Law 94-479

- ^ Bell, William Gardner; COMMANDING GENERALS AND CHIEFS OF STAFF: 1775–2005; Portraits & Biographical Sketches of the Usa Army's Senior Officer: 1983, Centre OF MILITARY HISTORY; UNITED STATES ARMY; WASHINGTON, D.C.: ISBN 0-16-072376-0 : pp 52 & 66

- ^ Ferling 2010, pp. 212, 264; Ellis 2004, p. xi; Higginbotham 1971, p. 211.

- ^ Buchanan 2004, p. 226.

- ^ "Commission as adjutant for southern district, 13 December 1752 [letter non found]". Founders Online. National Archives. March 28, 2016. Retrieved June 7, 2016.

- ^ "George Washington: The Soldier Through the French and Indian War". Independence Hall Clan. January 1966. Retrieved June 7, 2016.

- ^ "History Timeline". Col. Washington Borderland Forts Association via the Fort Edwards Foundation. February eleven, 2008. Retrieved June 7, 2016.

- ^ Order of the Secretary of the Army

- ^ "four.three The Creative person equally Citizen: Charles Willson Peale". StudyBlue. Retrieved June fifteen, 2014.

Sources [edit]

- Alden, John R. (1993). George Washington, a Biography. Norwalk: Easton Printing. ISBN9780807141083.

- Anderson, Fred (2000). Crucible of State of war: The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754–1766. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN978-0-375-40642-three.

- Anderson, Fred (2005). The War That Made America. New York: Viking. ISBN0-670-03454-ane.

- Bell, William Gardner. Commanding Generals and Chiefs of Staff (Center of Military History)

- Buchanan, John (2004). The Road to Valley Forge: How Washington Built the Ground forces that Won the Revolution . Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN978-0471-44156-4.

- Chernow, Ron (2010). Washington: A Life. New York: Penguin. ISBN978-one-59420-266-vii. OCLC 535490473.

- Ellis, Joseph J. (2004). His Excellency: George Washington. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBNane-4000-4031-0.

- Ferling, John Due east. (2010) [1988]. First of Men: A Life of George Washington. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0-19-539867-0.

- Fischer, David Hackett (2004). Washington's Crossing. Oxford, England; New York: Oxford University Printing. ISBN0-nineteen-517034-ii.

- Fleming, Thomas (2005). Washington's Hugger-mugger War. New York: Smithsonian Books. ISBN978-0-06-082962-ix. OCLC 237047336.

- Flexner, James Thomas (1968). George Washington in the American Revolution (1775–1783) . Boston: Picayune, Brown. OCLC 166632872. Second volume of Flexner'south four-volume biography.

- Flexner, James Thomas (1974). Washington: The Indispensable Man . Boston, MA: Footling, Brownish. OCLC 450725539. Single-volume condensation of Flexner's four-volume biography.

- Freeman, Douglas S (1948–1957). George Washington: A Biography . New York: Scribner. OCLC 425613. Seven volumes scholarly biography, winner of the Pulitzer Prize.

- Freeman, Douglas S; Harwell, Richard (1968). Washington . New York: Scribner. OCLC 426557. Abridgement of Freeman's multivolume biography.

- —— (1968). Harwell, Richard Barksdale (ed.). Washington. New York: Scribner. OCLC 426557.

- Grizzard, Frank E., Jr. (2002) George Washington: A Biographical Companion. ABC-CLIO, 2002. 436 pp. Comprehensive encyclopedia

- Higginbotham, Don (1985). George Washington and the American Military Tradition. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press. ISBN978-0-8203-0786-2. OCLC 489783125.

- Higginbotham, Don (1971). The War of American Independence: Military Attitudes, Policies, and Practice, 1763–1789.

- Ketchum, Richard M (1973). The Winter Soldiers. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. ISBN0-385-05490-4. OCLC 640266.

- Leckie, Robert (1993). George Washington's War: The Saga of the American Revolution. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN978-0-06-092215-three. OCLC 29748139.

- Lengel, Edward Grand. (2005). General George Washington: A Armed services Life. New York: Random House. ISBN1-4000-6081-8.

- Lengel, Edward G. ed. (2012) A Companion to George Washington, (2012), essays by scholars that emphasize the historiography

- Lengel, Edward G. ed. (2007) The Glorious Struggle: George Washington'due south Revolutionary War Letters (Smithsonian Books, 2007), Main sources

- Jerry D. Morelock (2002). "Washington as Strategist". Compound Warfare. DIANE Publishing. pp. 53–89. ISBN978-1-4289-1090-4.

- Royster, Charles. (1979) A Revolutionary People at War: The Continental Ground forces and the American Character, 1775–1783 (University of N Carolina Printing, 1979)

Espionage [edit]

- Crary, Catherine Snell. "The Tory and the Spy: The Double Life of James Rivington." William and Mary Quarterly (1959): 16#1 pp 61–72. online

- Harty, Jared B. "George Washington: Spymaster and General Who Saved the American Revolution" (Staff paper, No. ATZL-SWV. Ground forces Command And General Staff Higher Fort Leavenworth, School Of Avant-garde Military Studies, 2012) online.

- Kaplan, Roger. "The Subconscious War: British Intelligence Operations during the American Revolution." William and Mary Quarterly (1990) 47#1: 115–138. online

- Kilmeade, Brian, and Don Yaeger. George Washington's Secret 6: The Spy Band that Saved the American Revolution (Penguin, 2016).

- Mahoney, Harry Thayer, and Marjorie Locke Mahoney. Gallantry in action: A biographic dictionary of espionage in the American revolutionary war (Academy Press of America, 1999).

- Misencik, Paul R. Emerge Townsend, George Washington'southward Teenage Spy (McFarland, 2015).

- O'Toole, George J.A. Honorable Treachery: A History of US Intelligence, Espionage, and Covert Activeness from the American Revolution to the CIA (second ed. 2014).

- Rose, Alexander. Washington's Spies: The Story of America'due south First Spy Ring (2006)

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Military_career_of_George_Washington

0 Response to "Did Washington Command the Army Again in 1798 Again"

Publicar un comentario